I was reading a post on one of the West Virginia pages that I follow in which a person referenced “God willing and the creeks don’t rise.” in reference to rain and floods. Someone kicked in with “we say cricks”. They were both corrected by a good soul who told them that Creek, for the purposes of this phrase’s origin, meant Creek Indian.

But was the corrector correct?

I first heard of the notion of “creek” meaning “Creek” on a camping trip a couple of years ago at Barkcamp State Park in the area of Wheeling, WV. While there, we happened upon a museum dedicated to the Underground Railroad. There, we listened to amazing stories told by Dr. John Mattox. He told us about a young man who had been in the museum some weeks previous. They had a conversation in which the phrase was discussed and noted as being about the Creek Indians. As I was in a museum, I felt confident in repeating the knowledge to others as fact.

As was the case with Dr Mattox, the remark is routinely attributed to first being said by Benjamin Hawkins. It has been noted that the phrase should be correctly written as ‘God willing and the Creek don’t rise’. Because that is supposedly how the “original” author first wrote it. Hawkins, college-educated and a well-written man would never have made a grammatical error, so the capitalization of Creek is the only way the phrase could make sense. He wrote it in response to a request from the President to return to our Nation’s Capital and the reference is not to a creek, but The Creek Indian Nation. But did he really say the words quoted or was a phrase morphed to include him as the author?

To understand Hawkins, I read a little further into his history.

According to http://www.aboutnorthgeorgia.com/ang/Benjamin_Hawkins: Generally recognized as the Creek Indian “agent,” Benjamin Hawkins also held the title of General Superintendent of all tribes south of the Ohio River. During the course of his 21 years in these positions he would oversee the longest period of peace with the Creek, only to watch his lifetime of work destroyed by a faction of this Indian Nation known as the “Red Sticks” during the War of 1812.

The story of Benjamin Hawkins relationship with the Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians goes back to 1786, when America was working on solidifying its hold on the new nation. Threats not only from abroad, but internally as well, forced the fledgling nation to negotiate treaties with the tribes on the western frontier.

At the time Hawkins was Congressman, he joined other well known Southeastern American leaders in negotiating a major treaty with the Creek and Cherokee at the South Carolina city of Hopewell. Tensions between settlers and both tribes had been rising following the Treaty of Augusta and the land cessions of 1782-1783.

Following that treaty John Siever formed the state of Franklin from land previously claimed by North Carolina but never ceded by the Indian tribes. Siever, known as Nolichucky Jack to his friends, was as brutal to the Cherokee and Creek as they were to him, but Siever knew to frame his attacks as responses to incursion or wrongs.

The states involved sent Hawkins, Andrew Pickens (South Carolina), Joseph Martin (Georgia) and Lachlan McIntosh (Continental representative, Georgia) to negotiate a treaty to end the fighting. Signed in November, 1785, A Treaty With the Cherokee (the technical name of the Treaty of Hopewell) created the first rift between the Cherokee Nation and the Chickamauga Cherokee that would not end until the Chickamauga went West following the Revolt of the Young Chiefs.

Two years after the signing of the treaty, Benjamin Hawkins died at the site known as Old Agency. On his deathbed he married the Creek woman who had been his common-law wife.

So, if during the time of Benjamin Hawkins’ life, the Creek Indians were experiencing the longest period of peace, why would he fear that they would “rise”. The underscore of that sentiment would be that he married his common-law wife on his deathbed and she was of the Creek Indians.

At the same time there is some evidence that the creation of Fort Deposit (Fort Deposite) in Georgia was a cause of concern in that munitions and arms were stockpiled. The Creek so-called civil war of 1812 involving the Red Stick faction, and their combat North and South, appears to have been an impetus for that fort’s creation. The New Madrid earthquake (reputedly the largest in recorded history in North America) created the division between traditionalist Creek (Red Sticks) and those more willing to seek accommodation with the majority of the tribe. The resulting warfare and predictable civilian losses in the South reportedly gave rise (using the Southern frontier penchant for willin’ as opposed to the educated willing) to the phrase which was then likely mistakenly attributed to Hawkins due to his Native American connections.

According to World Wide Words, when asked if it meant Creek Indians, their expert responded with: “Quite certainly not. Every researcher who has investigated the expression has dismissed an Indian connection as untrue. The tale is widely reproduced and believed nevertheless. It’s worth looking into because of the way in which it has been elaborated in the version you quote.”

The researchers went on to cite two different publications in the 1800s in which the authors did not capitalize the word “creek”, leading one to believe they did not mean the people proper.

Feller-citizens — I’m not ’customed to public speakin’ before sich highfalutin’ audiences. … Yet here I stand before you a speckled hermit, wrapt in the risen-sun counterpane of my popilarity, an’ intendin’, Providence permittin’, and the creek don’t rise, to “go it blind!”

Graham’s American Monthly Magazine, Jun. 1851.

We are an American people, born under the flag of independence and if the Lord is willing and the creeks don’t rise, the American people who made this country will come pretty near controlling it.

The Lafayette gazette (Louisiana), 3 Nov. 1894.

Another publication, Proceedings of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge Jurisdiction, Volumes 88-89, coins the phrase: “‘if the Lord is willing and the creek don’t fire,’ we will so do”. That book was a 1908 publication and leans toward the thought of Creek Indian, even if not capitalized, because of the word “fire” (as in shooting guns).

Some newspaper clippings are harder to determine which meaning they meant.

Frederick, Maryland

18 Dec 1886, Sat • Page 2

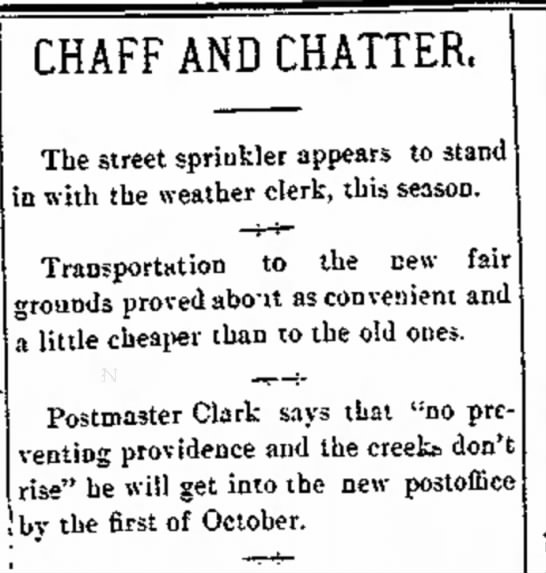

The clipping below from 1892 is a reference to flooding waterways not allowing the postmaster to get to his office.

Portsmouth, Ohio

06 Aug 1892, Sat • Page 1

I will continue to look for references to this phrase origin and would welcome discussion to prove (one way or the other) what the original author intended to mean.

Hey, enjoyed your post on this subject! I came looking because my self an my sis-in-law were discussing the quote today. She told me about the Creek Indian connection. I would point out that that the “permittin'” etc., does not automatically mean uneducated. I’m a member of the National History Honor Societ, and I often speak the same way. Trying to squeeze that g in at the end requires more effort than it’s worth. 😁 I need to start digging into this stuff again.